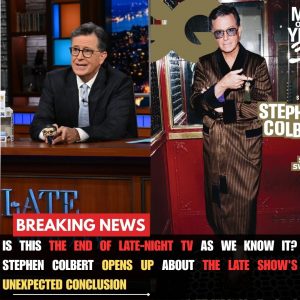

Stephen Colbert is by the pool at the Chateau Marmont in West Hollywood wearing bathing trunks, a robe, and nothing else. GQ’s idea, not his. It’s been about two months since CBS canceled The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. Twenty-four hours from now Colbert and his staff will win their second Emmy of the year, the first two that the show has won since Colbert started doing The Late Show. The crowd will give Colbert a standing ovation right at the beginning of the ceremony.

Right this second he’s in the robe, about to get into the pool, and holding a lit joint that I maybe think I see him smoking, but when I mention it later, this is his response: “You cannot prove that I was smoking unless you want to do a blood test right now.” Then he tells me to get a warrant: “Are you a cop?” (I am not a cop.)

When CBS canceled The Late Show, it had been the number one show in late night for the better part of nine years. CBS described the choice as “purely a financial decision against a challenging backdrop in late night. It is not related in any way to the show’s performance, content, or other matters happening at Paramount.” The other matters happening at Paramount at the time were a planned merger with Skydance Media (now complete) and a $16 million settlement the company had recently paid to President Donald Trump over a 60 Minutes–related lawsuit. Colbert, on air two days before his show was canceled, said that this kind of settlement “has a technical name in legal circles. It’s: big fat bribe.”

Colbert is not exactly new to causing national moments of controversy. In his previous guise as Stephen Colbert, right-coded pundit host of The Colbert Report, he once ran for president. He also gave a speech so memorably caustic in front of President George W. Bush at the 2006 White House Correspondents’ Dinner that the non-character version of Colbert stopped reading the news about himself entirely. One of many fun things about Colbert is that the same guy who goes on television and inspires the personal ire of multiple presidents is also a Lord of the Rings superfan, devout Catholic, and suburban dad. “My life’s an open book,” he tells me.

I tell him I believe him.

“Good. Then I’ve fooled you already,” he says.

When we speak, Jimmy Kimmel hasn’t yet been suspended and then reinstated. Colbert is at this point late night’s first and only casualty.

GQ: How’s work? Super normal?

STEPHEN COLBERT: Strangely, everything is normal because the show is never normal. I’ve got nine months of shows to do. I can’t be thinking about it ending in May. I’ve got to think about the show on Monday. So when you say, “How’s the show, perfectly normal?” Well, yeah. It wasn’t that normal when I had to tell everybody that the show was ending, but the next Monday I had to do a show.

Does nine months feel like a long time or a short time right now?

The end has a discernible shape, but it still seems like a long way away.

Can you describe that shape?

The image I have is a man walking toward me in the dusk and he’s got something in his hand, and I don’t know whether it’s a knife or an ice cream cone, but he’s asking me if I’d like a lick.

I can’t tell if this is a bit or this is real.

What are you talking about? Why would this be a bit? By the way, it is hard to tell whether things are real or a bit sometimes to me. Every day you have to come up with a bit about something that was real. So, after a while, it’s hard to tell what’s a bit and what’s real because you see other people engaging in performative behavior all the time, and it’s hard to know if they’re sincere about it. And, at a certain point, it doesn’t matter if they’re sincere about it because their behavior has an effect.

You’ve been attaching your mouth to the exhaust pipe of news for, I don’t know—

That sounds vaguely suicidal. “You’ve been running your car in the closed garage of media for 20 years, are you’re getting a little woozy?” Yeah, I’m getting a little woozy. Listen, it’s possible that George Cheeks [at the time, co-CEO of Paramount and the president and CEO of CBS] saved my life. I’ll get a little oxygen back into my brain.

I love what we do and I love the grind. You can only do one of these shows, do the jokes every night, year after year for 20 years, if you give a damn at all about what you’re talking about. And I do. But there is a sense of relief that I might not have to put on the snorkel and get into the sewer every day.

You have been doing this for a long time. Do you have any coping mechanisms when you kind of have to interact with the world so relentlessly?

Yeah. The show itself. The great thing about comedy, not to take anything away from drama, but the great thing about comedy is that you know when it works: The audience makes this noise with their mouth. And that can’t really be faked. And you get instantly a sense of we’re here together and that you’ve hooked up your jumper cables to them and that there’s an energy that goes to you to them and them to you. When it’s really working well, you walk offstage with more energy than when you walked onstage. I’ve never been sick onstage. I’ve been very sick. I did a show where I had a burst appendix and I did a double show. I didn’t know my appendix was burst. I didn’t know what was wrong with me, but I was sweating and thought I might pass out and I was in so much pain that I was crying in commercial breaks. But doing the show, I could just get through it. And I did two shows. I did a double show that night. And then afterwards my wife made sure that my driver took me straight to the hospital, and I got there and they said, “Oh, you have a burst appendix. We have to take this out right away.” But the point is that the show itself is a gift. That energy that you get back from the audience? Laughter is the best medicine. And boy, the only better medicine than that is making other people laugh.

And yet the show is ending.

And yet the show is ending. Really early on in the old Colbert Report, we liked the idea that the character didn’t know he was on a comedy channel because he took himself very seriously and he really was changing the course of human history with the tractor beam of his own justice. And so the way Jon Stewart would toss to me from the Daily Show, we would toss to the morning show on Comedy Central, which we called YAD, which stood for “Yet Another Day.” And I love the desperation of that, of having to go on and do yet another day. And yet, no matter how much I enjoy it or the audience might enjoy it, yes, the show is ending.

You found out in July. Have you wrapped your head around it?

No. No, no. Not at all. No. I mean, I have accepted it. I’ve wrapped my head around that. But in terms of how I feel about it, no, I don’t know because the shows go on. I don’t necessarily know how I’ll feel about it until I’m not doing it anymore, because it’s all-consuming.

What did you feel when you found out?

I was surprised. Listen, every show’s got to end at some time. And I’ve been on a bunch of shows that have ended sometimes by our lights and sometimes by the decision of other people. And that’s just the nature of show business. You can’t worry about that. You got to be a big boy about that. But I think we’re the first number one show to ever get canceled.

You guys have been number one since 2016.

Exactly. And I called a friend of mine who’s also in late night, and I was trying to work out my feelings and I said, “You got any thoughts on this?” And he goes, “No, no one’s going to have any thoughts on this. No one’s ever been the number one show for nine years in a row and then been canceled.” And so that surprised me. When I signed my 2012 contract for The Colbert Report, I went to my assistant, I said, “Hey, what’s our last show of 2014?” And she goes, “It looks like December 18.” I said, “Oh, good to know.” And I started writing that last show myself. Basically, the entirety of that last show was something that I thought of, really, in the next month. And then I thought I was going to leave that and go. I’ve been an actor my entire career. I had a whole show that I had planned out of what I was going to do, and it was actually going to involve that old character in a new job, and he would be like a central figure, but he wouldn’t be the only character in it. And I might still do it someday, but that was my plan. And then taking over for Letterman fell on my lap, but I had a plan of how to end it. I knew the songs we were going to sing, I knew the jokes we were going to do. I knew how I wanted it shot—everything.

This is not my choice. So I don’t know how we’re going to land this plane, but people have asked me, “Well, what do you think you’re going to do next?” And the cleanest and really fullest answer I can give you, not that I don’t have thoughts, is, the honest answer is, I just want to land this plane gracefully in a way that I find satisfying, given how much effort we’ve put into it for the last 10 years. That’s a long answer. You want shorter answers or is that okay?

No, I love a longer answer. This is real life. So when they called you and told you—

They didn’t call me and tell me! My manager told me.

No one called you?

No. They told him. They told him, and he told me. He said, “Hey, do you have 15 minutes? I’m going to stop by.” And I said, “Sure.” So I got off and I said to my assistant, I said, “Baby Doll”—because my manager is James “Baby Doll” Dixon—“Baby Doll wants 15 minutes in person?” Usually, like, five minutes on the phone is an hour with him. And I said, “I’m super tired, I’m really exhausted. Just make sure this doesn’t go too long.” So when 15 minutes comes by, my assistant texted me. I said, “It might be a little longer.” I was so tired. I was lying down on my couch with a pillow over my eyes going, “Hey, James, what’s going on?” I was prone. And he said, “This is going to be the last season.” So I sat up and was like, “Oh, okay. Well, that’s interesting. I did not expect that.” And then we talked for hours. Because you don’t have that moment very often. And then I went home and my wife, who was expecting me home in 15 minutes, and she said, “That was two and a half hours.” She goes, “What happened? Did you get canceled?” And I said, “Yep.” So we sat down, she got me a drink, and we sat and talked about like, “Okay, what do you want to do next?” That was it.

Did the explanation provided to your manager make sense to you? What was it?

That they’re getting out of the late-night space altogether because it’s no longer profitable for the network. And I said, “Well, if we can’t be, then no one can be.” And look, they run the business and I run the show, and far be it for me to tell them how to run their business, but I’ll stick with: I found it very surprising.

And did you find what they said plausible? Do you believe it?

Television’s in huge trouble. Maybe David Ellison [CEO of Paramount Skydance] will fix everything. No, no. Seriously. Maybe he will. Maybe he’ll fix everything. But it’s clear that television is in a lot of transitions. It’s been going on for a long time. But that’s not my end of the business. My end of the business is the jokes.

If I have the sequence of events correct, CBS’s parent company, Paramount, pays President Donald Trump a settlement of $16 million, which you call the bribe on air, and then—

Please don’t get me a lawsuit here. I said, “I believe that there is a name for that. And it would be: big fat bribe.”

Shortly after that the show is canceled.

Two days later.

And immediately, politicians like Elizabeth Warren and Adam Schiff come out and say words to the effect of: If this was politically motivated, the American people deserve to know.

By the way, everything you’re telling me right now, you have to tell me right now. I don’t

read about myself. Who’d you say?

Adam Schiff and Elizabeth Warren.

Well, good for them. I mean, that’s not my job. That’s not my reaction to it. My reaction as a professional in show business is to go: That is the network’s decision. I can understand why people would have that reaction because CBS or the parent corporation—I’m not going to say who made that decision, because I don’t know; no one’s ever going to tell us—decided to cut a check for $16 million to the president of the United States over a lawsuit that their own lawyers, Paramount’s own lawyers, said is completely without merit. And it is self-evident that that is damaging to the reputation of the network, the corporation, and the news division. So it is unclear to me why anyone would do that other than to curry favor with a single individual. If people have theories that associate me with that, it’s a reasonable thing to think, because CBS or the corporation clearly did it once. But my side of the street is clean and I have no interest in picking up a broom or adding to refuse on the other side of the street. Not my problem. So people can have their theories.

I have my feelings about not doing the show anymore, but you’d have to show me why that’s a fruitful relationship for me to have with my network for the next nine months, for me to engage in that speculation. I have had a great relationship with CBS. It’s one of the reasons why this was so surprising and so shocking that there was no preamble to this. We do budgets and everything like that. We’ve done cuts and stuff like that. So that’s why it was surprising to me, as I said, but I meant what I said [on air] the next night after I found out, because I couldn’t sit on it. They’ve been great partners. They really have. They’ve been very supportive. It took us six to nine months to find our legs. Even before people watched the show, we didn’t quite figure out what we wanted to do. It didn’t come fully assembled out of the box the way The Colbert Report did. And they stood by us and they were very supportive and they gave us what we needed and we found it and we delivered for them what we wanted. I want to do a good job.

I’m in show business. I want to do a good job for the network, and I’m really proud that we could do that for them. And that only made our relationship better. Why do you want to be number one? To brag? No—

I was going to ask if you’re competitive.

Well, yeah. Of course you’re competitive. But I really like the other guys. We’re all friends. The best reason to be number one is that the network does not fuck with you. That is the best reason to be number one. And we enjoyed nine unfucked years. Only supportive. Only great.

Earlier, you alluded to this kind of macro conversation of: Does the late-night format even make sense anymore?

They said it. I’m just telling you what they said.

I think there is a hardening wisdom around this idea somehow that the time for these shows has passed. I’m wondering if you’ve ever felt that doing your show?

No, not doing the show. I do the show with gratitude, we have a really great time. We love doing it with each other. We love all pulling on the same rope. I love being there with those 450 people in the Ed Sullivan Theater in a Broadway theater. We’ve done our best to deliver something that the network can monetize in some way. I thought we were successful at that. So, all things must pass. I think if there is a business reason for this, I know there’s been a change in ad rates since the strike, and I know that’s never really recovered from that. So that all makes sense to me. And I also know that these late-night shows are kind of like symphony orchestras. They need a certain amount of personnel to do them. You can’t really do a show in the Ed Sullivan Theater, 11:35 on CBS, with a band and sketches and field shoots and stuff like that, for the cost of a podcast. And if you look and say, “Oh look, this is what a podcast makes and this is what these shows make,” then you’re keeping these shows on because you love the form. So to me, it seems indispensable as part of some American’s experience or daily experience. But I can understand from a business point of view, they go, well, that is meaningless to me as someone who has to answer to a board of directors and investors.

This is going to sound, I think, more skeptical than I mean it to sound, but I’m curious what you feel like the great affirmative case is for a show like yours.

In other words, why should shows like mine continue to exist? Or like Kimmel or Jimmy or whatever? Well, we are like your friend who at the end of the day paid attention to what happened today more than you did. And then we curate that back to you at the end of the day. But it’s really more about how we feel about—or I, as the person who is the vehicle for that—how we felt about today. All those things that might’ve made you confused, angry, or anxious or happy or surprised or something like that. I share those feelings with the audience and they laugh or they don’t laugh. And there’s a sense of community there. And there are fewer and fewer of what, I don’t know who coined this term, but there are fewer and fewer of what you would call third spaces in our life. Not your home, not your work, but some other place we get together. And these late-night shows are for millions of Americans a third space to come together and think about the day.

I suppose another thing is, Hey, where do people go to talk about their book or their movie or their TV show, or if they’re a politician, their cause, or if they’re a philosopher, their idea, where do they go? Or a scientist, their discovery or their curiosity. And I know there are other places to go, but those are increasingly, however popular they may be, they’re more like subscriber audiences, more niche audiences as opposed to—however much there might be a balkanization of how people view television—it’s a general audience. You just turn on your TV. It’s just there.

People perceive me as this sort of lefty figure; I think I’m more conservative than people think. I just happen to be talking about a government in extremis. And so what I’m giving you is my reaction video to the day. And my reaction video is like The Scream, in a way, but with jokes. So that makes me perceived as more left necessarily than I am because I’m not sure what other reaction would be an honest one. It’s hard to have a balanced reaction to the idea of troops on streets of a city that actually is not undergoing an invasion.

And so those three things together is the beginning of a case of why these shows should exist. We broadcast to a general audience. There’s no entrance fee, there’s no subscription. You don’t have to look for us except on channel five or wherever you are. And we have a variety of different guests, a variety of different—it’s a variety show.

Prior to this show, you played a character for a long time. How has it been spending the last 10 years as—would you call the guy who hosts your show yourself?

Yeah, it’s pretty close. I mean, it’s a performance persona. There are times when it’s very close to me, especially if there’s something that cannot receive a joke. There are things that will not receive the matrix of our desire to do comedy. And I choose not to talk about tragedy on my show because I think that’s sacred. But there are things that are unavoidable that are happening in our country. And because I talk about what’s happening in America today. I mean, just the other night with the tragic shooting of Charlie Kirk, that required me to, at the very top of the show, just to say, listen—

And that was you.

That’s me. I mean, me isn’t always sad, horrified guy, but as a performer, it’s probably sesqui- autobiographical. It’s one-and-a-half times me because you need that little extra energy to reach out and kind of hold the interest of the audience. But it’s me. I don’t generally say or do things that I don’t mean on the show unless I’m in character, like in a sketch. Whereas at the Colbert Report, it was almost nothing. Basically it was Catholic and Lord of the Rings were the only two things that we had in common.

How do you look back on that character now?

Fondly. I mean, it was enjoyable to do. A lot of people thought you couldn’t sustain it. And I always thought I could, because a mask is such a gift for me, at least as a performer, because really all my training in my entire career until I did the show was as an actor. And The Colbert Report was an almost 10-year scene that I did. And we had a bible for the character. We kept a running bible. What does he believe? What does he not believe? What’s his back history? What’s the relationship with other people? Why was he a friend of Pinochet Ugarte? All kind of things. We were writing it as this ongoing narrative where nothing we did should be contradicted by other things we did for that character. And also he was—as much as people said he was a critique of certain pundits, some right, some left, some neutral—he was a confession of my own appetites. Who doesn’t want to be right all the time? Who doesn’t want to be the most important person? Who doesn’t want to be: “I know I am America!” To give into the indulgence of that privilege.

I had forgotten until recently that there was a moment where people really thought you and Jon Stewart were going to save the republic somehow.

I promise you, we did not share that feeling. Especially when reflecting back on the Rally to Restore Sanity slash March to Keep Fear Alive—he was doing the Rally to Restore Sanity, and I was doing the March to Keep Fear Alive, and I like to remind him that I won. That we kept fear alive.

To me, it is bound up in that Obama-era optimism that at least at the moment has been sort of brutally repudiated by subsequent events—that kind of faith in that character and what he was going to be able to accomplish.

Repudiated by some people. I don’t despair. Spaire literally is from Spero: “I hope.” The motto of my home state, South Carolina, is Dum spiro spero: While I breathe, I hope. And despair itself is a sin. You are not allowed to despair because that means you know all ends and not even the wise know all ends, to quote my friend Gandalf. But one of the things that I said to Jon toward the end when we were doing those shows together, I said, “You know what’s funny to me? Is everybody thought that we wanted to be players.” When we did that, people were like, “Well, they’re trying to actuate the youth vote!” Nothing. No part of it. We saw that was a new context. It had nothing to do with us trying to be political players. There’s a great moment in the Lord of the Rings. Again, I can relate anything back to The Lord of the Rings. It’s one of the last lines of my special skills on my résumé. But there’s a moment when Gandalf says, “One of our great hopes here is that it is not entered into Sauron’s darkest dreams that we would ever want to destroy the ring.” And so I always felt that John was Frodo and I was Sam, and all I wanted to do was help him. We wanted to throw the ring in the fire. Now, what is the ring? I guess it’s power for the sake of power, as opposed to power for the sake of service.

Do you feel like that desire came with you to the Late Show?

Purposefully not, at first. When I first came over, I really wanted to find a way to lay down that sword and shield down by the riverside, because it does me no good. I’m not a warrior, I’m a comedian. I really don’t want to be the guy in the front of the parade with a banner. That’s of no interest to me. And people can lay that on you as something that they want you to do. But I think it’s important to not drink your own Kool-Aid there and just remember that your job is, you’re an entertainer. But because I put it down without replacing it with something, I literally did the first six months of the show going: What should we do tonight? What’s my attitude tonight? What’s my point of view tonight? And it really wasn’t until the political campaign of 2016 really started cooking that I realized again that you cannot do these shows unless you’re talking about something you really care about, that’s in the daily conversation.

And what did you care about?

I cared about what at the time seemed like a dangerous thing: to clothe someone like Donald Trump, to clothe him in the power and dignity of the office. Because then people will only see the clothing of the dignity and the power of that office. And really, the dignity is the thing, in some ways, it’s most dangerous, because then it provides dignity and status to everything the person does. It’s a very powerful form of dignity in that office. And it piqued my interest and it gave us a compass heading of what to talk about every day. We tried to avoid politics actually at first, because we’d done 10 years of it, and we were lucky that per force in an election year, you can’t ignore it. And it seemed like there was an urgent story.

Do you enjoy having to react to Donald Trump every night?

No. I am grateful to be able to react because, again, it’s a selfish endeavor. I get a lot out of going out there and doing jokes about what happened today, no matter what happened today. But especially if I see something that I think is detrimental to the American people and to the reputation of a country that is irreplaceable. There’ll never be another America. But that doesn’t mean it’s invincible. Well, that weighs on your heart, just as an American to see that, depending on your point of view. And I’m grateful to go do the jokes. But your question was?

Did you enjoy reacting to him?

I enjoyed going and doing the jokes and being with the audience when he wasn’t in office. I think we went three years without saying his name. I don’t think I said his name for three years. And if he made news, we would just come up with some nickname. No, I love not talking about him.

When he was reelected, was there a part of you, not the citizen part, but the professional part, that was like, I can’t believe we have to do this again?

I mean, that would be all parts of me. I mean, I know how to titrate poison. You titrate poison with your own jokes and your own editorial stance on it and how you push back on what you think is the lie that is telling you this is vitamins, but there’s no doubt that

it’s poisonous.

Do you ever allow yourself to feel: “I’m going to be free soon. I’m not going to have to think about this”?

Well, I mean, I’m an American. I’m not going to be free of it. I’m still going to care. I’ll miss the ability to go out there and make jokes.

You’ll miss it.

I will miss every aspect of my job other than wearing makeup.

Do you feel like it’s become intrinsic to your identity somehow to be the host of the show? Is there any, “Who am I without this?”

No, I know who I am without this. I didn’t do any of this until I was 41. I got the Colbert Report when I was 41. I was really old to get one of these jobs. And then by the time I got this gig, which I never planned on because I’m not a standup, I’m not from the background that usually gets one of these gigs. And I was 51 when I took it. That’s really old for somebody—it’s not really old, but you know what I mean. It’s late to take it. So that is only to say, I was married with all my children before I was Stephen Colbert, that anybody would know. And my identity is associated with that. And the family I grew up with and my faith.

You have talked about being younger and struggling with anxiety and depression and finding basically, and please correct me if I paraphrase this wrong, but basically finding the solution in work and performing—

I’ve had recreational anxiety for a lot of my life, starting in my teens. I had different answers then. Checking out, basically. Just never doing my schoolwork, only reading the books I want. Eventually smoking a lot of weed, stuff like that, which I passed through and moved on. But when I was 29, I had an honest-to-God nervous breakdown. I dunno what the clinical term is these days. Psychological collapse. I had an implosion. And I was newly married, didn’t know what I was going to do. Suddenly, I was panicked that I had chosen something to do with my life that wouldn’t give me the life I wanted. And I don’t mean that I wouldn’t be successful, but that somehow the life I had chosen would not allow me to be a husband and a father in the way that I wanted to be, because of the demands of how hard it is to, well—the sacrifices you have to make. And I tried Xanax and stuff like that, but I could still feel the gears smoking. You know what I mean? I couldn’t hear them anymore, but I could smell them smoking. And so I stopped and I just rawdogged it. And I woke up one morning and my skin wasn’t on fire. I’m like, what was different? Oh, it was the first day of rehearsal for the new show.

That’s what I’m asking—

And that’s what I’m answering. It’s just a long answer. It’s not, like, comedy keeps me sane. No. Making things, making anything—I probably could do it if I was going to build a boat. It puts my feet on the ground. I love process. And suddenly I woke up one day and I thought: Oh my God, I get to go work. And then I thought: Oh no. Now I can never stop working.

I used to think that. Now, I actually think that a lot of those things that caused me great anxiety, I have already passed through the fire of that trial in that stage of my life. And I’m not a young man full of doubt anymore. And I think that if I stopped work, if I chose to next May, I’m done and I get a catamaran and just sail, I don’t think that would come back. I really feel like that’s no longer who I am.

Is there a part of you that’s tempted to get a catamaran and just sail when May comes around?

Yeah. Yeah, there is.

Do you fantasize about walking away from show business?

No. No. Because I love creating things and I still want to work with the people I work with. I don’t know how you work with 200 people, 210, something like that, right? It’s an enormous amount of people. I love them. And I want to continue to do that with them to the degree that I can. And I want to find that with other people too. I just love making things.

So you’re not even like, “We’ll see.” You’re saying, “We’re going to keep going. We’re going to make something else.”

Yeah. Why not?

Zach Baron is GQ’s senior special projects editor.

This interview has been condensed and edited from a video you can see here.

Get the Man Of the Year issue — Guaranteed. Subscribe now to secure your copy and one year of GQ for only $2 $1/month.