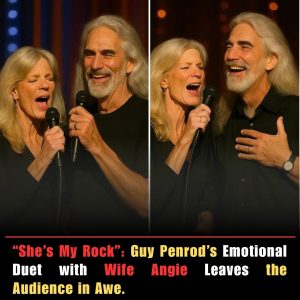

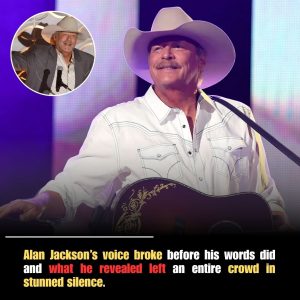

In the dim hush of a community center gymnasium on the outskirts of Newnan, Georgia—far from the flashbulbs of the CMA Awards or the roar of sold-out arenas—a wooden stage creaked under the weight of a moment heavier than any platinum plaque. Alan Jackson, the stoic sentinel of traditional country whose baritone has soundtracked three decades of heartache and honky-tonks, stepped forward without fanfare. No entourage, no emblematic white cowboy hat tilted just so, no entourage of publicists scripting the spotlight. Just a man in khakis and a plain button-down, his silver hair catching the faint glow of overhead fluorescents, extending a simple check to a wide-eyed program director. “Maybe this will help somebody find their song,” he murmured, his Georgia drawl soft as a summer rain on tin. The amount: $500,000, earmarked not for headlines, but for the raw, unpolished dreams of 200 underprivileged kids scattered across the rural South—children clutching thrift-store notebooks filled with scribbled verses, their futures hinging on the strum of a secondhand six-string.

That unassuming handover last Tuesday, captured only by a single local news crew sworn to discretion, has rippled outward like a stone skipped across a still pond, touching lives from dusty backroads to bustling Nashville boardrooms. It’s the kind of quiet philanthropy that defines Jackson at 66: deliberate, devoid of drama, a testament to a career built on authenticity rather than algorithms. While peers chase TikTok virality and Vegas residencies, Jackson—retired from the road since his 2020 dementia diagnosis but never from the giving—chose the shadows, reminding a genre often accused of glossing its grit that country’s true currency is compassion. And in small-town classrooms from Macon to Mobile, that check is already tuning young hearts to the frequency of possibility, proving one legend’s legacy can launch a thousand more.

The genesis of this gift traces to Jackson’s own origin story, etched in the red clay of his youth. Born in 1958 to a family of sharecroppers and shipyard welders in the hardscrabble hamlet of Newnan, Alan was the sixth of ten, raised in a three-room house where music was salvation, not spectacle. His mother, Ruth, a factory seamstress with a voice like polished oak, would gather the brood around a battered console radio, crooning Hank Williams and George Jones to drown out the din of poverty. By 12, Alan had saved for a pawn-shop guitar, its strings buzzing like fireflies in the night, teaching himself chords by ear under the eaves. “Music wasn’t a hobby; it was how we held on,” he reflected in a rare 2017 interview with The Tennessean, his eyes distant as the Chattahoochee. That instrument became his ticket out—first to local bars, then to the neon vein of Nashville in 1985, where a demo tape landed him at Arista Records and launched anthems like “Chattahoochee” and “Gone Country” that redefined the ’90s sound.

But success, for Jackson, was always a boomerang: what it gave, it demanded he return. His Sir Survival Fund, quietly stewarding donations since 1993, has funneled millions into causes from cystic fibrosis research (in honor of a late crew member’s daughter) to hurricane relief after Katrina ravaged his beloved Gulf Coast. This latest largesse targets Music Dreams Inc., a grassroots nonprofit bridging the gap for low-income youth in the Bible Belt, where public school arts programs have been gutted by budget axes. Founded in 2018 by former session guitarist Maria Delgado, the organization equips kids aged 8-18 with instruments, lessons, and songwriting workshops in underserved counties—places where football fields outnumber fine arts facilities, and a kid’s biggest stage is the back of a flatbed truck at a family reunion. “These children aren’t statistics; they’re symphonies waiting to be scored,” Delgado says, her voice cracking over a Zoom from her cluttered office in Athens, Georgia. “Alan’s gift buys 500 guitars, funds two years of scholarships, and builds three mobile studios that can roll into the holler. It’s not charity—it’s choreography for their futures.”

The handover itself was a masterclass in understatement, unfolding at the Newnan Community Center during a low-key fundraiser disguised as a potluck supper. Attendees: about 50 locals—farmers in feed caps, teachers with thermoses of sweet tea, a smattering of wide-eyed tweens fidgeting with donated ukuleles. Jackson arrived unannounced, slipping in through a side door after a 90-minute drive from his Franklin, Tennessee ranch, where he tends to horses and health with the same steady hand. No podium, no playlist of his 40-plus No. 1s; just a folding chair, a manila envelope, and that trademark humility. As the check changed hands—presented to Delgado amid a smattering of claps—he lingered for an hour, not as icon but as uncle, kneeling to tune a young girl’s banjo and sharing a story about his first botched open mic: “Fell flat on ‘Don’t Rock the Jukebox,’ but the crowd laughed with me, not at. That’s when I knew—music’s about the mess, too.” One beneficiary, 14-year-old Elijah Hayes from nearby LaGrange, captured the exchange on his flip phone: a blurry clip now cherished like a family relic, showing Jackson’s callused fingers brushing the boy’s as he handed over a starter acoustic. “He looked at me like I was already writin’ hits,” Elijah whispers, strumming tentatively in his trailer home, the guitar case propped against a wall papered with faded posters of Johnny Cash.

Word leaked slowly, as Jackson intended—no press release, no Instagram flex. It bubbled up through Music Dreams’ newsletter, then snowballed via word-of-mouth in Nashville’s tight-knit troubadour circles. By Thursday, the story had permeated the Grand Ole Opry grapevine, prompting a cascade of quiet emulations. Blake Shelton, the Oklahoma showman who’s traded stadiums for a coaching chair on The Voice, matched the donation with $250,000 from his Friends and Heroes Foundation, quipping in a handwritten note to Delgado: “Alan’s the real deal; I’m just tryin’ to keep up without trippin’ over my boots.” Kacey Musgraves, the ethereal wordsmith whose “Golden Hour” nodded to Jackson’s influence, hosted a virtual song circle for 20 Music Dreams scholars, her golden voice weaving their fledgling lyrics into a collaborative track uploaded to SoundCloud—already at 100,000 streams, with proceeds looped back to the cause. Even international echoes: A Dublin-based trad-country collective, inspired by Jackson’s “Midnight in Montgomery,” pledged Euros equivalent to outfit a sister program in Ireland’s rural Gaeltachts.

Critics and chroniclers of country’s soul are hailing this as a pivot point. “In an industry chasing crossover cash-grabs, Alan’s act is a reset button,” muses historian Robert Oermann, author of A Century of Country. “He’s not performing philanthropy; he’s living it—echoing the Carters and the Snows who built this genre on barn dances and benevolence.” Oermann points to data from the Country Music Association: Arts education funding in Southern states has plummeted 30% since 2010, leaving 1 in 5 rural kids without access to instruments. Jackson’s intervention—amplified by peers—could seed a renaissance, with early signs blooming. In pilot classes post-donation, attendance spiked 40%, and one Mobile middle schooler, 12-year-old Sofia Ruiz, penned “River Run Dry,” a haunting ballad about her migrante mother’s sacrifices, now workshopped for a youth showcase at the Ryman next spring.

For Jackson, sidelined by the progressive neuropathy of Charcot-Marie-Tooth since going public in 2021, these gestures are lifelines. Confined more to his 1,200-acre spread—stocked with longhorns and a home studio rigged for remote collaborations—the Hall of Famer channels his fire into foundations, his latest album Don’t Rock the Jukebox: The Anniversary Edition (reissued last month) donating royalties to youth initiatives. “Fame’s a freight train—loud and leavin’ tracks,” he told American Songwriter in a sparse email exchange, his words measured against the fog of fatigue. “But givin’ back? That’s the slow dance that lasts. I see myself in those kids—the scared boy with a pawned pawnshop dream. If my sunset buys their sunrise, hell, that’s the encore I never earned.”

Bunnie XO, the unflinching Nashville podcaster and wife to Jelly Roll, amplified the tale on her Dumb Blonde episode Friday, interviewing Elijah and Delgado live. “Alan’s the ghost in the machine—the one who don’t need the glamour to glow,” she drawled, her Tennessee twang thick with tears. “In a town full of sequins and scandals, this is the stitch that holds us.” Listeners responded in kind: A GoFundMe for Music Dreams, seeded by the buzz, hit $100,000 in 24 hours, with donors from oil riggers in Oklahoma to execs in L.A. penning notes like “Alan’s whisper is our wake-up call.”

As twilight settles over Newnan’s fields, where Jackson once chased fireflies before chasing fame, the impact unfolds in fragments—a first chord struck in a shotgun shack, a lyric jotted on a lunchroom napkin, a dream deferred no more. Elijah Hayes, practicing scales by flashlight to spare his mom’s electric bill, pauses mid-pluck: “Mr. Jackson said it’s okay to start small. So I’m startin’—one note at a time.” Somewhere, in the ether where “Livin’ on Love” lingers, Alan Jackson smiles that soft smile. He came with gratitude, alright. And in return, he’s gifted country a harmony deeper than any hit: the sound of beginnings, boundless and bright.